Part 2 – Return to Training Guidelines for Collegiate Athletes Following the COVID-19 Shut Down

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a significant restructuring of the way in which Canadians work and live, with sporting activities worldwide being significantly impacted. Sport in most academic settings has been cancelled for the fall 2020 semester resulting in a 10 month withdrawal from most competitions, and in some cases, practice settings. As a result, there exists some uncertainty as to appropriate practices for maintaining athlete preparedness during the shutdown. It is important at this time to continue to support athletes in their development and to recognize the role that the S&C coach can play managing their wellness and performance.

If properly managed, the cancelled season presents an opportunity for university and college sports teams to maximize their athlete performance potential through the development of strength, power, speed, agility, and energy systems in off-field training. With the guidance of an S&C coach, and a focused period to train in a healthful and rested state, athletic gains can be maintained or improved depending on individual needs.

Prolonged periods of low activity are a risk factor that must be managed during this period of shutdown. The evidence is clear that significant deconditioning not only decreases performance ability, but also increases injury risk when returning to play (1,2). It is imperative that this risk be mitigated as part of a return to play strategy.

There are no restrictions on S&C contact time in Canada, and S&C coaching is not restricted to certain seasonal periods within the Canadian university calendar, therefore this can be leveraged for the benefit of athletes.

It is recommended that strategies to safely open existing training facilities be developed while also increasing the capacity to train athletes remotely. It is believed that this can be readily accomplished by implementing the guidelines outlined herein.

As coaches, there is a responsibility for managing the health and wellbeing of our athletes. The benefits of a team training environment go beyond improving physical qualities in student-athletes, and include mental health and wellness qualities as well. The S&C coach may play a pivotal role in assisting in the maintenance and growth of overall athlete wellness, which at this time, is critical.

There is a significant amount of difficulty associated with decision making for collegiate sport at this time given the uncertainty of the risks of COVID-19. We recognize that there are more unknowns then knowns when it comes to understanding the best approaches to working with athletes during the pandemic. We therefore are developing guidelines that may permit the flexibility of institutions to work within a continuum of risk in their approach to athlete conditioning.

We have reached out to institutions across Canada, from British Columbia to Nova Scotia, to identify those that have made progress on Return to Training (RT) planning, and the common themes consistent between institutions. However, although several common themes are outlined below, it is important to note individual differences and approaches were identified based on relative level of risk, provincial guidelines, size of the institution, student athlete enrollment, and facility size. The recommendations made herein are a reflection of those approaches beginning with a specific video overview from York University.

The guiding principles for return to training require a focus on three major questions:

- How do we prevent infection transmission between athletes?

- How do we ensure the safety of the staff?

- How do we manage any exposure that may occur?

There are many unknown variables that limit the ability to understand the nature of transmission that can occur in a variety of training settings and where the greatest risks exist. We do know that transmission is greater in certain settings when infected individuals are present. As a result, procedures can be created to mitigate risk of spread, and manage any exposure issues if they occur. Ultimately, solutions to these questions require the implementation of a stepwise plan for RT that includes the following:

Step 1: Development of a Return to Train Committee

Step 2: Personnel Education and Training

Step 3: Facility Preparation and Management

Step 4: Training Scheduling

Step 5: Communication and Quality Control

Step 1: Development of a Return to Train Committee

The development of a RT performance plan will require a collaborative approach. The management of team performance planning should occur through the establishment of an integrated group of stakeholders that should include one representative from the coaching staff, an S&C coach, a member of the sports medicine team, an individual representing facilities management, and if available, ancillary service providers such as a dietician, psychologist, physiologist, etc. This RT committee will then establish the plan and procedures for off-season training that will include the following:

- Space access and scheduling

- Facility layout and flow

- Personal hygiene practices

- Testing and monitoring protocols

- Exposure and tracing protocols

- Quarantine and isolation plans

- Athlete wellness

Each committee will have a lead that will work within the Athletics Department to ensure that the team is achieving the following:

- Following local, provincial and federal guidelines for operations

- Collaborating with institutional risk management and legal staff to identify liabilities

- Implementing policies consistently between teams

- Incorporating best practices identified by professional associations and sporting organizations

The S&C coach may be a likely candidate for fulfilling the lead role on this committee as they would overlap between RT committees for each sport. It must be recognized that the organization and management of this team will have a significant time commitment which must be calculated into the individual workload.

Step 2: Personnel Education and Training

Education should be provided to all athletes, coaches, and staff prior to accessing training services. It should be delivered in a flexible manner so as to minimize face-to-face contact. Education may take on many formats, including; webinars, live online meetings, written policy and procedure documents, powerpoint slides, or audio recording. The approach to education may differ for coaches and athletes. Education may be delivered in modules which may include a discussion of procedures related to the following:

- Space access and scheduling

- Facility layout and flow

- Personal hygiene practices

- Testing and monitoring protocols

- Exposure and tracing protocols

- Quarantine and isolation plans

- Athlete wellness

Education is a critical element of quality control and risk mitigation. Participation in the education process should be tracked. Implementing a reporting method to the RT committee may be helpful to confirm education is shared with each team. Again, the S&C coach may be an ideal person to take a lead role in the process of education and quality control.

Step 3: Facility Preparation and Management

A key element of the safety plan is the development of facility operation procedures that manages infection risk within a training context. Evidence suggests that the two major avenues of potential contamination are via airborne aerosolized water vapor droplets, and by direct contact with contaminated surfaces. In an S&C setting, both of these risks are enhanced due to the nature of the equipment used, and high athlete ventilation rates.

As part of the facility safety plan, consideration should be given to the following:

- Equipment cleaning and maintenance

- Air quality control

- Resources for personal hygiene

- Facility access

- Individualized training spaces

- Use of common areas

- Quality control procedures

The S&C coach will have a significant role in the implementation of the RT facility plan. It is recommended that an individual external to the RT committee audit quality control and compliance procedures to ensure safety standards are being met.

Step 4: Training Scheduling

Perhaps the biggest challenge S&C programs will face is the scheduling plan. To optimally service a team would require 2-6 training sessions per week. Most training spaces will have implemented social distancing plans that will significantly reduce the training capacity. As a result, the number of hours per week needed to accommodate all student athletes will need to be extended dependent on the number of athletes that are onsite. Each institution we consulted with are considering guidelines for group gatherings in their respective provinces, and in most cases, are considering the use of individual training areas, and whether an outdoor area can be used to increase athlete numbers.

In most cases, each team can determine the training hours needed by the simple formula:

Total weekly training space hours = Total # athletes / # training spaces x # hours per session x # days per week

In addition to facility scheduling, there will be a need to host online training programming for athletes not on-site, those concerned with health risks of RT, or if gym availability is limited. The number of athletes that will be offsite varies greatly between institutions we contacted. The number of online contact hours can be calculated using the same equation as above. As many athletes will have limited access to equipment offsite, it may be possible to share online sessions between teams as the program may be simplistic in design and easily scalable.

The S&C staffing requirements for on-site training have not been firmly established. General coach to athlete ratios for university sport in Canada vary from 1:10 to 1:15 dependent on the institution. With further risk management requirements, the ratio that exists during training sessions may have to change. In cases where athletes are significantly spread out, a lower ratio may be required. However, recognition should be given to the increased exposure risk to coaches that may exist with a lower ratio, as the total number of training sessions would have to increase.

Time required for meetings, program design, coach collaboration and athlete tracking should be calculated into staffing needs. Some institutions indicated that an S&C coach should only be scheduled with 65% of their time on the floor coaching, with no more than 4 hours of coaching consecutively. To complicate this, some Provinces are mandating ‘In Bubble’ training rules which means a coach can only train the same group of people each week. The goal of this approach is to minimize exposure and facilitate potential infection trafficking. An example would include one coach responsible for Monday and Wednesday team sessions, and another assigned to Tuesday and Thursday workouts. S&C coaches should check with their provincial guidelines to insure they are compliant.

It is possible that some programs will experience scheduling bottlenecks that will result in a limited ability to service the entire athlete population. If the number of athletes training at any one time is so low that the number of hours required to service all of them will not fit into a traditional work week, the plan has to be revised to be made workable. Institutions may need to consider implementing servicing levels to take into account programs at highest risk of injury and prioritizing sports to ensure physical preparation needs are able to be met.

Step 5: Communication and Quality Control

The key element to successful implementation of a RT safety plan will be the utilization of effective communication strategies between coaches, players and stakeholders related to procedures, progress, risk, and changes. It is likely that planning will have to be revised with less notice than usual so it is critical that all parties receive effective communication on a regular basis. The communication medium selected must be accessible and consistent. Processes for collecting grievances and responding to those issues should be very clear.

Of the institutions consulted, the chain and methods of communication varied, however each institution had a strategy in place. The RT Committee should formulate and implement the communication strategy and schedule regular meetings that should be adhered to. All participants should be accountable for reviewing any updates and there should be a single portal for this.

The time required for implementing this communication strategy must be carefully considered by the S&C staff. With some institutions requiring S&C service for over 10 teams, the workload associated with communication can be significant.

As part of the communication strategy there should be a mechanism in place for evaluating the effectiveness of the implementation of the safety plan. A system of audits should be designed and monitored by a third party to insure lapses in safety are addressed. Outcomes of the audits should be distributed to all stakeholders in order to encourage continued vigilance.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND SAFETY PLANNING

With all that is unknown regarding the transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, we are relying largely on World Health Organization (WHO) and Provincial Public Health guidelines for risk management and safety planning for RT. Although it is likely that the guidelines will change over time, there is enough information available to establish training risk scenarios for RT.

Most provinces have established a phased reopening plan for all businesses, including the training of athletes (3,4). The guidelines for collegiate athletes within each province vary, and are not comprehensive, but generally follow this path:

Phase 1

- Outdoor training with groups limited to five participants with social distancing

- No equipment use

- Indoor training of Provincial Sport Organization (PSO) accredited athletes where social distancing can be applied with a maximum number of participants capped at 5 per group

Phase 2

- Outdoor training with groups limited to 10 participants

- Equipment use, but not shared

- Indoor training of Provincial Sport Organization (PSO) accredited athletes where social distancing can be applied with a maximum number of participants capped at 10 per group

Phase 3

- Indoor training with groups social distancing up to 50 athletes

- Full equipment use

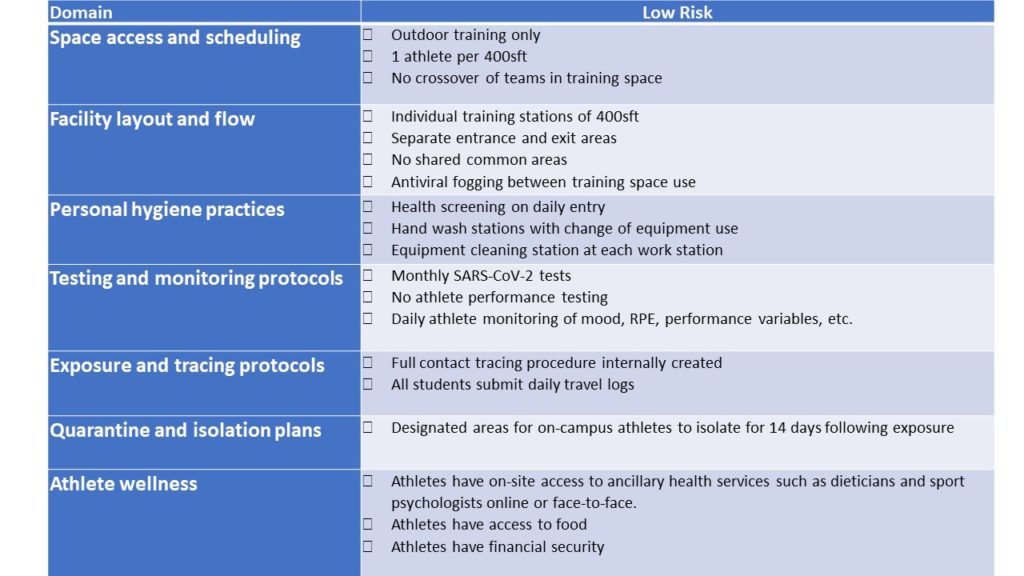

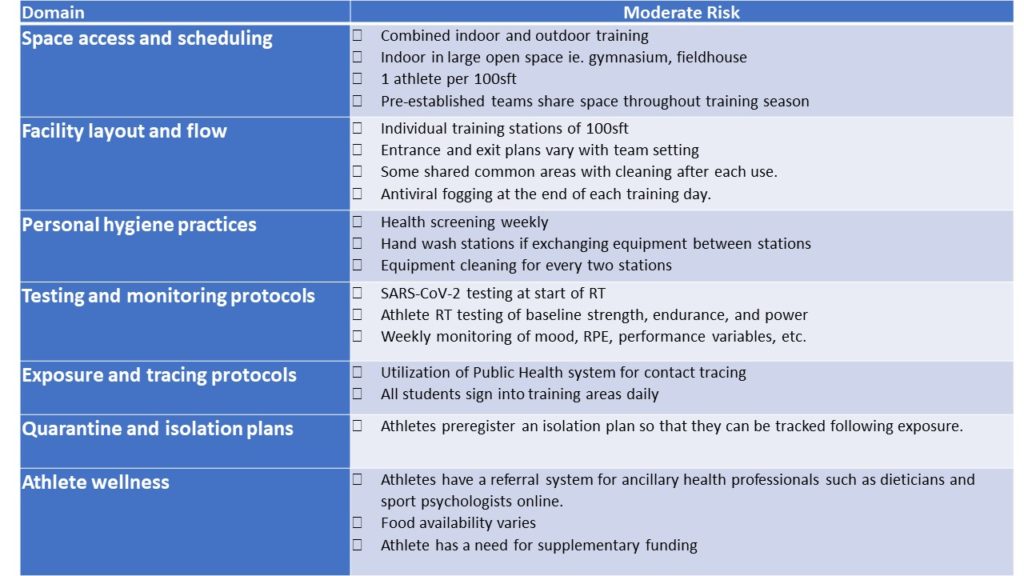

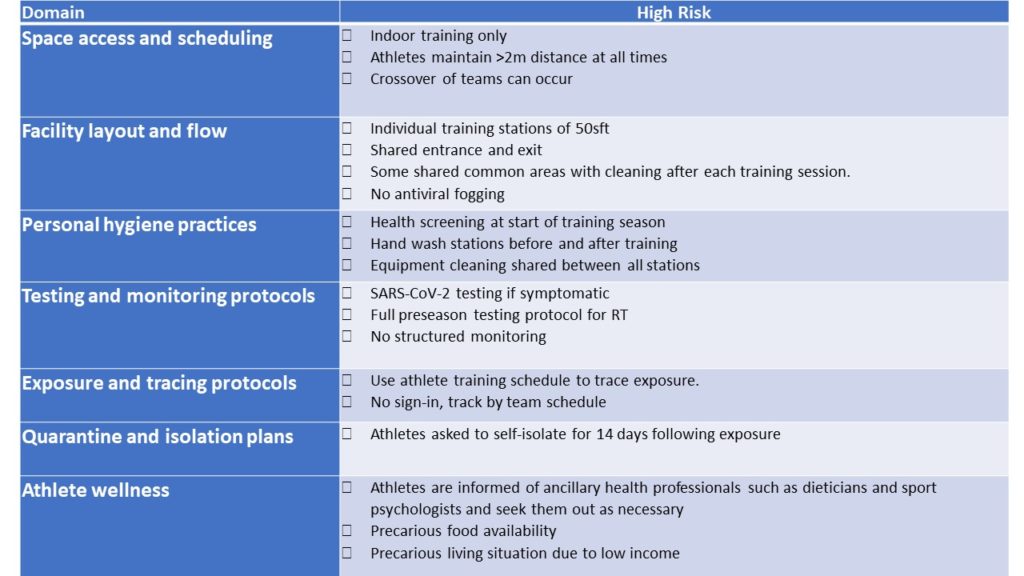

The best starting point is to review your provincial guidelines (see Provincial and Territorial Resources). However, beyond the guidelines, each institution must formulate their own RT plan that fits within their needs. There are no evidence-based guidelines specifically related to COVID-19 for RT scenarios at this time. To assist in the planning process we have therefore identified S&C RT scenarios where safety can be managed along a risk continuum. Table 1 outlines the stratification of planning in the management of differing levels of risk. Each institution will have identified their tolerance to risk, and this risk is likely to vary between institutions. As a result, each institution will have to select procedures that match their perceived risk tolerance.

Tables 1 to 3 are not intended to be used to evaluate the risk of a training environment. They should instead be used as more of a risk menu when selecting procedures to enact in a training space. In the tables, RT procedures have been classified into low, moderate, and high risk in seven different domains. The classifications of risk represent a continuum for each domain. The high risk classification is not indicative of putting athletes in harm’s way, but simply reflects possible scenarios where it is harder to guard against pathogen transfer.

In some cases, a low risk solution may not be attainable, and only a higher risk option exists. In this case, the higher risk option can be implemented but perhaps offset by a lower risk procedure paired with it. For example, in most cases, training outdoors in its entirety is not feasible, and the indoor space may be small with a limited number of workstations. In that case the RT committee could implement more low risk testing and monitoring procedures to offset the density of athletes in the training space.

One of the most challenging issues in risk stratification is the determination of square footage per athlete and absolute distance between training stations. This is further complicated when training space is relatively small and many athletes need to be serviced. Some programs have created recommendations for the number of athletes per square foot (sft) of training space. Again there are no specific guidelines for this. Provincial guidelines are for a minimum of 2m separation between individuals. WHO guidelines have set the acceptable distance without a mask as 1m (5). With the increased ventilation rates of exercising athletes, it is unclear what distance is ideal.

Generally, an 8 foot by 8 foot training platform with loading area is considered 100sft. When placed side by side this provides for greater than 2m separation between athletes, which will meet provincial guidelines. Some work stations, such as bench press, may be 6 foot by 7 foot, so approximately 50sft with loading area. Again, lifters would be able to maintain the 2m recommended separation, however there would be more shared “breathing space”. Note that in all of these scenarios, there is no consideration for a spotter, therefore safety racks must be used, and athletes will need to be taught how to perform controlled bailing techniques or modify training loads as needed. Early stage training should have few loading parameters where bailing is necessary.

Table 1: Low risk stratification for RT planning.

Table 2: Moderate risk stratification for RT planning.

Table 3: High stratification for RT planning.

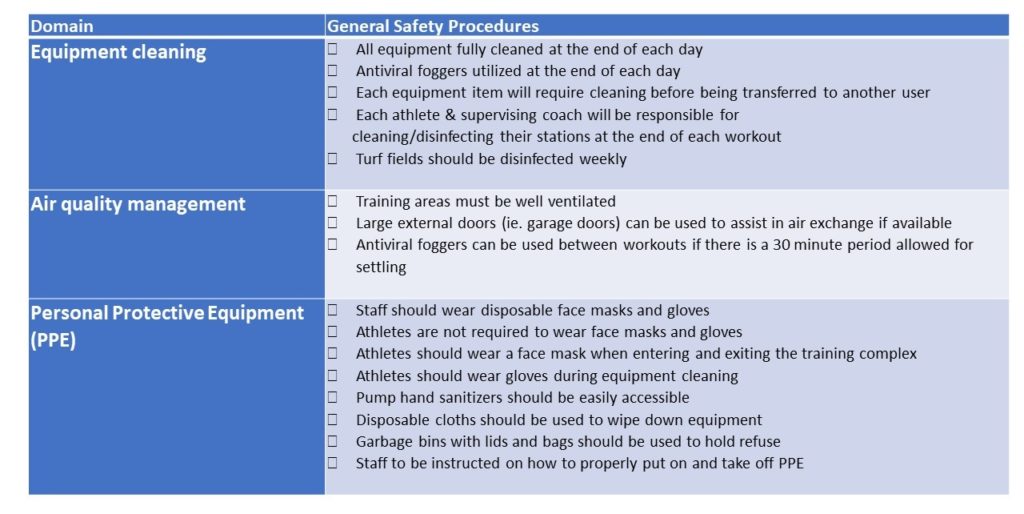

FACILITY PROCEDURES

As part of the RT process, the set up and management of the training areas will be altered to meet the acceptable risk level of each institution. Although best practices and standards have not been formalized, and are changing regularly, several institutions have developed some general and personal guidelines (Tables 4 to 6).

These general guidelines are not absolutes, and are suggested based on feedback from the institutions interviewed when preparing this article. Additionally, they are designed as a guide based off of information communicated thus far by the provinces and the WHO. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that they are best practices, adequate, or excessive. Again, each institution must assess their tolerance to risk and develop procedures that best manage these tolerances.

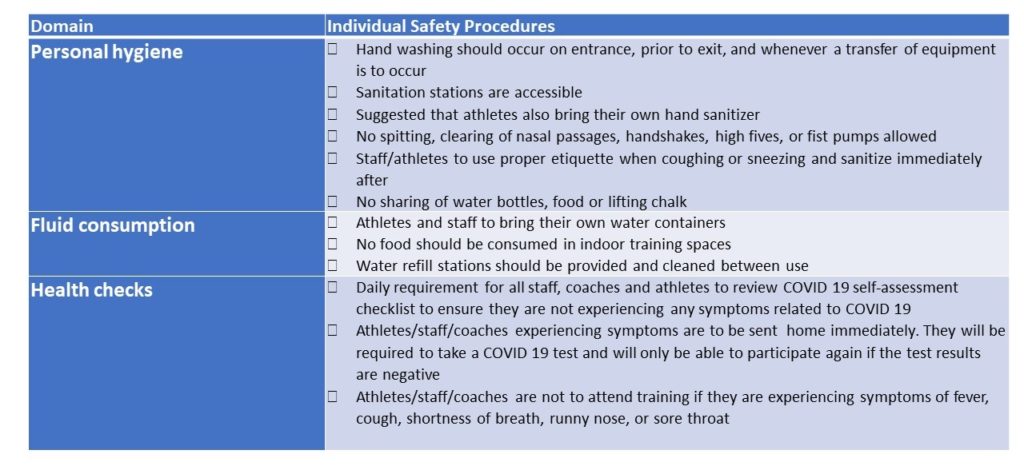

Table 4: General safety precautions that exist in institutions facilitating exercise programming.

Table 5: Individual safety precautions that exist in institutions facilitating exercise programming.

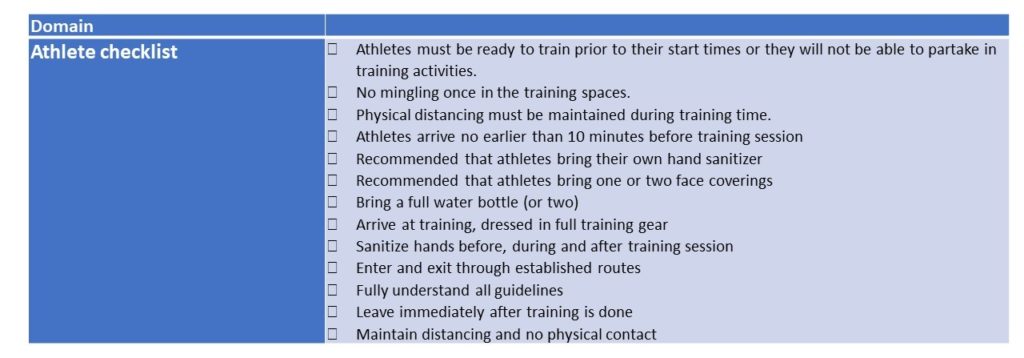

Table 6: Athlete safety checklist that exist in institutions facilitating exercise programming.

MANAGING TRAINING WORKLOAD

Several studies have identified loss of physical function following various periods of detraining (6,7,8,9, 10, 11, 12). Guidelines for reintroduction of training are not well established following prolonged periods of detraining in otherwise healthy athletes.

Several collegiate and club programs have initiated some gradual RT and early data suggests that motor skill and power return quickly, while maximum strength, strength endurance and power endurance take longer to recover. These deficits will manifest themselves during repeated exhaustive work bouts, such as maximal sprinting, and can result in intense soreness, cramping, and possible muscle strains. These observations would suggest that pre-existing motor engrams are easy to reprogram, whereas the rebuilding of muscle structure and metabolic function require a period of weeks to reach physiological significance.

During the isolation period, each athlete will have experienced a different level of deconditioning. As a result, each athlete will have a different tolerance to training upon return. In theory, best practice would include pre-RT testing of strength, endurance and power, however in some cases this may increase the risk of injury as testing could exceed physical tolerance to load.

One strategy that could assist in athlete RT is administering a history questionnaire that will assess the frequency and intensity of training of each athlete during the shutdown. If an athlete was participating in less than two structured, high intensity exercise sessions per week in the previous two months, you could make the assumption that they should be at a low level of physical capacity and therefore need to be more gradually reintroduced to training. In contrast, if the athlete had access to their own training space and equipment that they used three or more days a week, they could likely be fully reintegrated into programming with minimal transition.

Consideration would have to be given to some of the details of training participated in such as; speed vs speed endurance, agility vs agility endurance, submaximal vs maximal plyometrics, loaded vs unloaded power, maximal vs endurance strength training, and load bearing endurance vs non load bearing endurance. There is a significant difference in stress response between these training modalities and it may be necessary to track this in order to determine where gaps in training exist that could predict injury risk or performance limitation later in training.

Reintegration into programming could be defined as entering fully scheduled S&C workouts and/or team practices. S&C coaches must work with the sport coaches to ensure a gradual reintroduction to activity. There must be an integrated plan so as to prevent the doubling of workload and competing goals. In cases where athletes will start into practice at the same time as strength training activities, athletes should progress their speed, agility and conditioning through sport practice with minimal ancillary field/court work. In either case there should be a gradual increase in volume during the first few weeks.

Gradual return to training should generally not last longer than four weeks, and in some cases, athletes may be prepared for full reintegration after two weeks of base workouts. There are no exacting standards for determining this. Each S&C professional should use athlete perceived exertion, level of soreness, willingness to train, and performance progress as a guide to ongoing readiness. There are several symptoms of excessive workload that can be used as a guide:

- nausea or vomiting during training

- muscle cramping

- muscle soreness persisting more than 2 days

- poor daily performance progress

- loss of athlete motivation or fear of workouts

A simple approach to athlete monitoring for this would be to track session and exercise RPE between workouts and observe the RPE dropping for a given workload.

The guidelines for gradual return to training load in deconditioned athletes have not been formalized and could vary significantly.

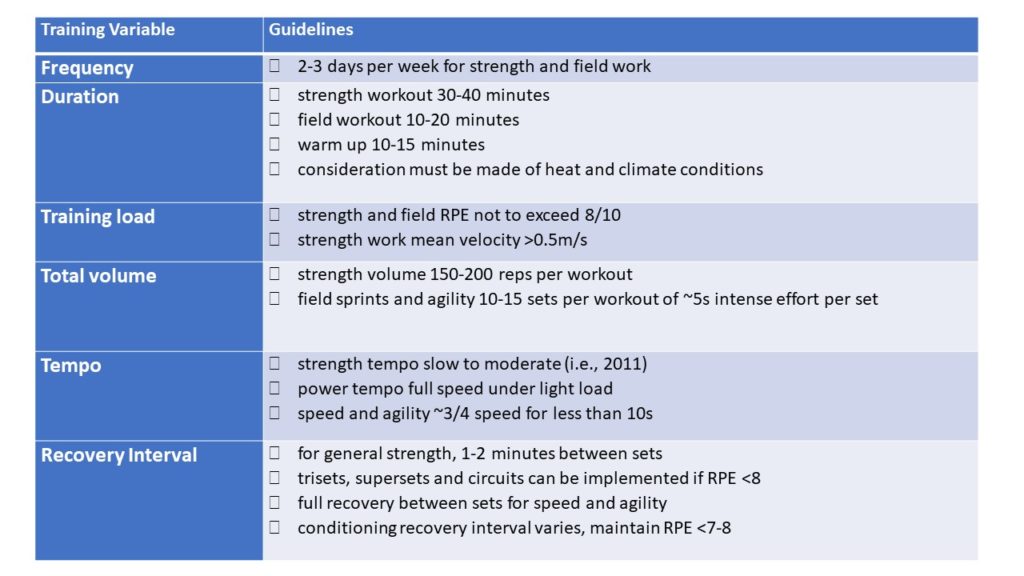

Table 7 provides some very general approaches to consider with the first week of training. Training loads and volumes can then be gradually increased each week dependent on athlete tolerance.

Table 7: General programming guidelines for the first two weeks of RT.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 pandemic offers significant challenges to collegiate sport programs, however it also provides an excellent opportunity for maximizing athlete potential through well designed S&C programming. The S&C staff are a critical component of the athlete RT process and should play a major role in RT planning and implementation.

The planning and implementation of the RT process will be complex, and may require significant increases in the administration time of S&C coaches. Additionally, there may be an increase in staffing necessary to administer these plans.

Formal guidelines for RT from the provinces and WHO are good starting points; however, each institution should identify their level of risk tolerance and choose procedures that best meet this tolerance. Decisions should not be made unilaterally, but instead should involve an integrated committee approach so that all aspects of performance can be considered.

There should be a gradual return to training load that sport and S&C coaches work together to establish and monitor effectively. Through careful planning, effective communication, and quality control procedures, the risk of exposure and transmission of the virus will be minimized and prevent any unwanted disruption of athletic programs. Programs that are most effective at implementing the RT plan will have a significant advantage over their competitors when sport resumes.

AUTHOR BIOS

Trevor Cottrell, PhD, CSCS. Dr. Cottrell is a professor of Kinesiology and Health Promotion at Sheridan College. His education includes an undergraduate degree in Kinesiology from the University of Waterloo, a Masters degree in Exercise Science from Northern Arizona University, a doctoral degree in Physiology from the University of Arizona, and postdoctoral work at Queen’s University. He has been a practicing strength and conditioning coach for 28 years and currently coaches an Olympic weightlifting program in Guelph, Ontario. Dr. Cottrell is the current Chair of the CSCA Education Committee.

Sam Eyles-Frayne. Sam is the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach at York University. Her education includes an undergraduate degree in Kinesiology from the University of Waterloo, a Masters degree in Kinesiology from the University of Guelph and a Certificate in Human Performance Training from Sheridan College. She has worked with several Olympic, Provincial and Collegiate organizations over the past 10 years. Sam is a Canadian Ambassador for Fast and Female and is currently an Advisory Member, as well as an Education Committee Member of the CSCA.

References

- Andreato, L.V., Coimbra, D.R. & Andrade, A. (2020). Challenges to Athletes During the Home Confinement Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. Strength and Conditioning Journal. 42(3):1-5 DOI: 10.1519/SSC.0000000000000563

- Baker-Davies R.M. et al. (2020). The Stanford Hall Consensus Statement for Post COVID-19 Rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med: DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596

- Government of Ontario. A Framework for Reopening our Province. https://files.ontario.ca/mof-framework-for-reopening-our-province-en-2020-04-27.pdf

- National COVID-19 Return to High Performance Sport Task Force. COVID-19 Return to High Performance Sport Framework. https://www.ownthepodium.org/getattachment/Resources/COVID-19-Resources/Canada-COVID-19-Return-to-HP-Sport-Framework-May-2020.pdf.aspx

- World Health Organization. Advice on the Use of Masks in the Context of COVID-19:Interim guidance. Health Emergencies Preparedness and Response. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak

- Garcıa-Pallarés J., Sanchez-Medina L., Pérez C.E., et al (2010). Physiological Effects of Tapering and Detraining in World-class Kayakers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42:1209–1214.

- Joo C.H. (2018). The Effects of Short Term Detraining and Retraining on Physical Fitness in Elite Soccer Players. PLoS One 13: e0196212, 2018.

- Koundourakis N.E., Androulakis N.E., Malliaraki N., et al (2014). Discrepancy Between Exercise Performance, Body Composition, and Sex Steroid Response After a Six-week Detraining Period in Professional Soccer Players. PLoS One 9: e87803, 2014.

- Mujika I. & Padilla S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of Training-induced Physiological and Performance Adaptations. Part I: Short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med 30:79–87.

- Mujika I. & Padilla S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of Training-induced Physiological and Performance Adaptations. Part II: Short term insufficient training stimulus. Sports Med 30:145–154.

- Ormsbee M.J. & Arciero P.J. (2012). Detraining Increases Body Fat and Weight and Decreases VO2peak and Metabolic Rate. J Strength Cond Res 26:2087–2095.

- Pritchard H., Keogh J., Barnes M., McGuigan M. (2015). Effects and Mechanisms of Tapering in Maximizing Muscular Strength. Strength Cond J 37:72–83.

Provincial and Territorial Specific Resources

Alberta – Alberta’s Relaunch Strategy. https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-relaunch-strategy.aspx

British Columbia – Gyms and Fitness Centres: Protocols for Returning to Operation. https://www.worksafebc.com/en/about-us/covid-19-updates/covid-19-returning-safe-operation/gyms-and-fitness-centres

Manitoba – Restoring Safe Services: Manitoba’s Pandemic and Economic Roadmap for Recovery. https://www.gov.mb.ca/covid19/restoring/phase-two.html

Newfoundland and Labrador – Nlife with COVID-19. https://www.gov.nl.ca/covid-19/alert-system/alert-level-2/

New Brunswick – NB’s Recovery Plan. https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/corporate/promo/covid-19/recovery.html

Northwest Territories – GNWT’s Response to COVID-19. https://www.gov.nt.ca/covid-19/

Nova Scotia – Reopening Nova Scotia. https://novascotia.ca/reopening-nova-scotia/

Nunavut – COVID-19 GN Update. https://www.gov.nu.ca/executive-and-intergovernmental-affairs/news/covid-19-gn-update-june-15-2020

PEI – Renew PEI Together. https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/en/topic/renew-pei-together

Quebec – Public Health Authority Guidelines Concerning the Resumption of Indoor and Outdoor Physical and Sports Activities Carried out Individually and in Teams. https://www.quebec.ca/en/tourism-and-recreation/sporting-and-outdoor-activities/resumption-outdoor-recreational-sports-leisure-activities/public-health-authority-guidelines-resumption-sports-leisure-activities/

Saskatchewan – Gyms and Fitness Facilities Guidelines. https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/treatment-procedures-and-guidelines/emerging-public-health-issues/2019-novel-coronavirus/re-open-saskatchewan-plan/guidelines/gyms-and-fitness-facilities-guidelines

Yukon – COVID-19 Information. https://yukon.ca/en/covid-19-information