What Are The Limitations of Youth Resistance Training?

Despite numerous position papers, a growing body of research evidence, and the prevalence of school-based strength and conditioning programs, there continues to be significant concern regarding the use of strength training for youth athletic development. These concerns are fed by anecdotal beliefs that there is increased injury risk in this population, concerns about growth delay, and an overall denial of the adaptability of young athletes. Unfortunately, these beliefs do not match the research currently available, or the outcomes being measured in the sports such as weightlifting and powerlifting. The adaptations we are now observing in youth resistance trained athletes are beyond what any would have believed possible just a few decades ago.

Exactly where and when the mythology surrounding youth resistance training originated is debatable, although it appears to have been seeded in the 1950’s. At that time, America led the world in weightlifting, but there was significant negative emotion towards this sport for reasons that are too extensive to discuss here. As a result, sport coaches, doctors, and those working in the rehabilitation industry were quite suspicious of the strength sports, and weight training in general, and were therefore eager to negate its value in society. Time and ongoing research have since dispelled this mythology, however since coaches, teachers, and doctors passed on these beliefs over a 60 year period, it has been pretty ingrained into the lexicon of Western society.

There are several position papers and review articles examining the safety and efficacy of youth resistance training and the conclusion is virtually unanimous in that youth weight training does not increase risk of injury, may decrease risk of injury, will improve physical literacy, and poses no long term risks (1-6). In 2020, Dr. Cochrane published an informative summary on this very topic with the CSCA (7).

Despite all that is now published, research is still lagging on the best approaches to training this population. Performing research in this population is difficult for the following reasons:

1. Research ethics boards consider it a high risk population.

2. Most ethics boards will demand an extremely conservative approach to training in effort to mitigate risk and liability, often resulting in protocols with low training stimulus.

3. It is difficult to access this population. Schools will not assist you in research due to liability concerns, and you are reliant on parents to adhere to protocols.

4. Youth athletes are often inconsistent in attendance and can lose interest easily.

5. The emotional maturity and motivations of children varies widely resulting in varying efforts of children during test days.

6. Invasive techniques such as muscle biopsies are not viable in this population, limiting the understanding of mechanisms of adaptation.

7. Changes in lean body mass are difficult to assess as most body composition algorithms are not designed for youth.

8. Biological age and normal developmental gains in performance are major confounding factors that are difficult to control for and may offer alternative interpretations of outcomes.

9. It is hard to change incorrect assumptions once they are published. Research tends to be conservative and approvals tend to ask researchers to follow common methodologies in a given area.

Due to these factors, current standards for the training of youth athletes may be lacking. The current recommendations generally include high repetition, low load activities where body weight is the main load during the lifts, even though bodyweight can vary significantly in these age groups. 1-2 sets of 10-15 repetitions is the common recommendation (8-10). Physical literacy is the focus, learning to control the body during tasks such as running, jumping, and throwing, and learning weight room specific movements such as squats, lunges, hinges, pushing and pulling. The belief is that development of motor skill is of primary importance, and that true strength development will occur in the later teenage years during a predicted window of trainability of approximately 15-18 years of age (11).

Here is one example of provincial guidelines circulated to physical educators in elementary schools for students 4 to 13 years of age (12):

- Only small hand-held fixed weights up to 2.2kg (5lbs) maximum (e.g., moulded plastic dumbbells) can be used in fitness activities.

- Weights must be appropriate to the size and ability of student.

- Resistance training for the development of endurance can be done emphasizing high repetitions and/or low weights.

There are limitations to these recommendations when considering the differences between age groups and developmental maturity. Although challenging, recommendations related to chronological, biological, and emotional maturity would benefit student physical literacy.

It is this author’s opinion that the current standard guidelines for youth resistance training fall short of what the true adaptation potential is for this population. If you look at the recommendations being made, the reality is that it is no different than working with any lifter, young or old. Everyone should start with low weight, and bodyweight exercises performed at high repetitions to learn the movement skill, then progress load as ability allows it. The problem is that the recommendations tend to discourage the loading of youth, while favoring it in adults. The argument is that youth lack the capacity to adapt to higher loads due to hormone profiles and maturity. To load youth can be perceived as venturing outside of industry standards.

By taking this approach, coaches may actually be missing critical opportunities for adaptation that could drastically impact athlete performance in their adolescent years. With appropriate progressive loading in youth, that is then built upon during pubescence, you can gain strength, power and motor skill advantage that will be retained through all years of competition and beyond into adulthood.

The current model whereby most athletes do not start progressive performance training until the late teenage years falls far short of where athletes could be upon reaching university. Imagine a world where a Canadian university strength coach does not have to spend two years coaching up an athlete in the weight room in order to build their physical potential to a level where they can tolerate the demands of their sport. Instead, they are handed an individual that is physiologically capable of advanced play, needing only to focus on the sports skills that will make them successful.

The question then becomes “What are the limits of adaptability to strength training in youth populations?” If you look at the research evidence, the answer is a firm “we’re not sure”. The validity of strength studies in this population are continuing to improve thanks to the efforts of pioneers such as Avery Faigenbaum. Despite this, many studies in youth are so short-term and controlled that they restrict the stimulus provided, and do not allow for time to fully test the strength potential in young athletes.

The sports of Olympic weightlifting and powerlifting are starting to provide us with clues as to the extent of potential in this population. With a recent growth of popularity of these two sports, more youth are being drawn to them and the lifts being posted are impressive.

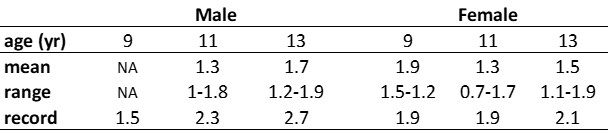

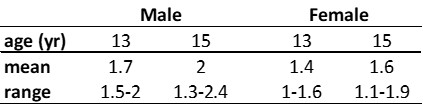

An analysis of 2019 data for USA Weightlifting and USA Powerlifting indicates that youth (<15 years) have tremendous potential for strength gains that are similar to many adult new lifters. When normalized to body weight, it is common to see the squat lift performed at above 1.5 times bodyweight in males and females with some records approaching triple body weight, which is phenomenal at any age (Table 1). Similarly, the clean and jerk lifts at recent national championships also are in excess of 1.5 times bodyweight, which is a dream of most university strength coaches (Table 2).

Table 1: Results of the 2019 Youth National Powerlifting Championships and USA Powerlifting youth records were normalized to body weight (kg lifted/kg bodyweight) and compared across weight classes (13). Presented here are the mean and ranges of normalized load lifted for the squat discipline across all weight classes within two different age categories for males and females separately. The best all-time record for the squat is also included as normalized data.

Table 2: Results of the 2019 Youth National Weightlifting Championships were normalized to body weight (kg lifted/kg bodyweight) and compared across weight classes (14). Presented here are the mean and ranges of normalized load lifted for the clean and jerk discipline across all weight classes within two different age categories for males and females separately.

In an interview with two Olympic weightlifting coaches in North America, who have developed their own children to the Olympic level, I was able to gain further insights into what the potential is for strength development in youth and how it may be is best achieved. Dalas Santavy is a former world level Olympic weightlifter and has four children, three boys and one girl, currently between the ages of 17 and 23. His sons started lifting between the ages of six and eight, and his daughter at the age of 10. All started with a technique emphasis on the major lifts but were allowed to progressively load as technique allowed it using traditional weightlifting programming. All moved onto Junior National ranking and the oldest is currently Canada’s top male lifter. Although detailed records were not kept, it was felt that their gains were roughly linear over time with a slight bump during puberty that was offset by proportional weight gain. In sport, the children excelled at all levels and none have suffered major injuries, although patellar tendinopathy was common.

Mike Burgener is also a former world level Olympic weightlifter that also has four children, three boys and one girl. Although they are now fully grown, with families of lifters of their own, they all started lifting between the ages of 6 and 8, all excelled in lifting, and his oldest son competed at the world level. He too started with dowel weights and progressed load with technique proficiency. He actually developed a technique scoring system and would have his youth athletes compete for technique scores instead of max lifts. His experience led him away from traditional high rep models to finding significant success with 10 sets of three reps. The focus of this approach being a repeated opportunity to practice high skill movements under load without fatigue. His children did not experience injury and also progressed in strength more or less linearly with a slight increase during puberty that was offset by bodyweight. The biggest challenge discussed was related to motivations around training at young ages. Kids can easily lose interest in the work required to train.

What can be concluded from these anecdotes, and the existing achievements of youth athletes in strength sports, is that phenomenal strength and power gains can be obtained through quality coaching instruction and progressive loading similar to what is used in adult populations. These gains transfer to sport and seem to have minimal injury risk. As a result, the combination of professional experience with current research leads to an evidence-based decision that there is little modification to training necessary for youth lifters other than motivational factors that may affect their adherence to a program.

Youth should be progressed as technique and movement skill allows, and can be loaded in similar progressions as adults. Efforts should therefore be made to re-address guidelines that exist, so that youth athletes have more potential exposure to quality training needed to progress them to higher levels of performance.

Author Bio – Dr. Trevor Cottrell is currently the professor for the Bachelor of Health Sciences (Kinesiology and Health Promotion) program at Sheridan College. He is also a member of the CSCA’s Executive Board and the Chair of the CSCA’s Standards Committee.

References

1) Lloyd, R.S., et al. Position statement on youth resistance training: the 2014 International Consensus. Br J Sports Med 2013; 0: 1-12.

2) Faigenbaum, A.D., Kraemer, W.J., Blimkie, C.J., et al. Youth resistance training: updated position statement paper from the National Strength & Conditioning Association. J Strength Cond Res 2009; 23: S60-79.

3) Baker, D., Mitchell, J., Boyle, D. et al. Resistance training for adolescents and youth: a position stand by the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association (ASCA). 2007 https://www.strengthandconditioning.org

4) Lloyd, R.S. Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D. et al. UKSCA position statement: youth resistance training. Prof Strength Cond J 2012; 26: 26-39.

5) Behm, D.G., Faigenbaum, A.D., Falk, B., and Klentrou, P. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position paper: resistance training in children and adolescents. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2008; 33: 547-561.

6) Stratton, G., Jones, M., Fox, K.R. et al. BASES position statement on guidelines for resistance exercise in young people. J Sports Sci 2004; 22: 4, 383-390.

7) Cochrane, A. Youth Resistance Training: Facts And Fictions. Canadian Strength and Conditioning Association. Accessed January 3, 2021. https://canadianstrengthca.com/youth-resistance-training-facts-and-fictions-review-article/

8) American Academy of Pediatrics. Strength training by children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2008; 121: 835-840.

9) Faigenbaum, A.D., Myer, G.D. Resistance training among young athletes: safety, efficacy, and injury prevention effects. Br J Sports Med 2010; 44: 56-63.

10) Behringer, M., vom Heede, A., Yue, Z et al. Effects of resistance training in children & adolescence: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2010; 126: 1199-2010.

11) Long Term Athlete Development 2.1. Canadian Sport for Life. Published May 2017, accessed January 3, 2021. http://sportforlife.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/LTAD-2.1-EN_web.pdf?x96000

12) OPHEA. Ontario Physical Activity Safety Standards in Education. Accessed January 3, 2021. https://safety.ophea.net/elementary/curricular/fitness-activities

13) USA Powerlifting. Lifting Database. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://usapl.liftingdatabase.com/competitions-view?id=2308

14) USA Weightlifting. 2019 Youth National Weightlifting Championships. Accessed June 21, 2020. https://www.teamusa.org/USA-Weightlifting/Events/2019/June/27/National-Youth-Championships