An Interview with Track Coach Les Gramantik: Part 1

In this article, CSCA Advisory Team Member Carla Robbins shares about her connection, and the details of her first interview, with track coach Les Gramantik in this three part series.

Introduction

In 2010, three years after I moved to Calgary, and while completing my undergraduate degree at the University of Calgary, I moved in with someone named Rachael McIntosh. Rachael was a Canadian National team heptathlete at the time, who had just moved to Calgary to train with a new coach. This was after changing her sport pathway and letting go of her scholarship at the University of Pittsburgh after one year. One might ask why someone would make such changes? The reason was Coach Les Gramantik.

Rachael told me many stories about Coach Gramantik, but it wasn’t until 2013 when I started working for the Canadian Sport Institute Calgary (CSIC) that I got to meet Coach Gramantik, and put a face to the name. I have known Les for 10 years, and his mentorship role in my life has grown a lot. To this day, we often go for coffee to discuss coaching, track, training philosophies, and the evolution of our industry.

One year ago, I decided to start an interview series with Coach Gramantik to capture his coaching philosophy in an informal manner. I thought to myself, “If I’m one of the closest coaches to him, and I don’t start writing down his stories and training beliefs, who will?” To note, what is to follow, if slightly divergent from our typical CSCA article structure.

In preparation for the interview, I reached out to Dr. David Smith (Doc), a former professor of mine and notable researcher and exercise physiologists for advice. His answer:

“Carla, you only need to ask one question, then just listen.”

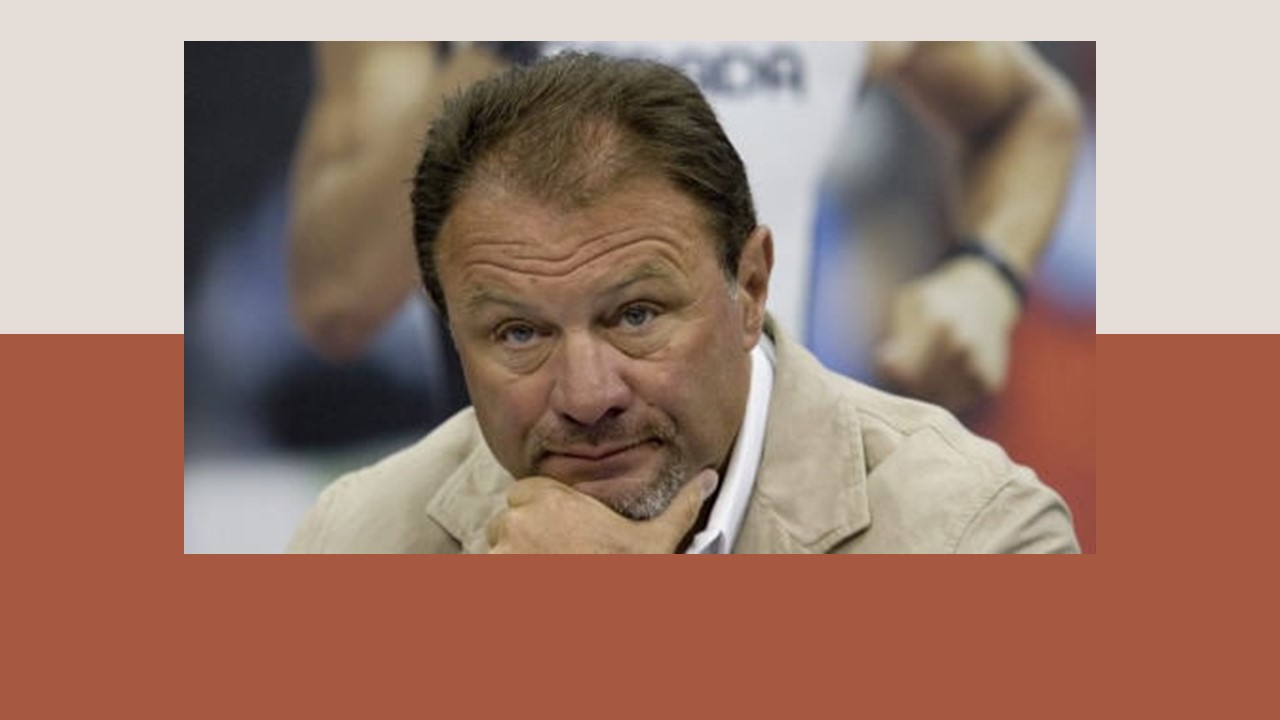

About Les Gramantik

Les Gramantik is regarded as one of the most successful and influential track coaches in the world. With a coaching career spanning over four decades, Coach Gramantik has led numerous athletes to Olympic medals, world records, and national championships. Some notable athletes that he has worked with include:

- Jessica Zelinka: Jessica Zelinka is a Canadian heptathlete who worked with Coach Gramantik in the lead-up to the 2012 Summer Olympics in London. At the Olympic trials, Zelinka set a new Canadian record in the heptathlon with a score of 6,599 points, which stood as the national record until 2018. Zelinka went on to finish in 7th place in the heptathlon at the 2012 Olympics, a career-best performance for her.

- Damian Warner: Damian Warner is another Canadian athlete who has worked with Coach Gramantik. Warner is a heptathlete who has won multiple world championships and Olympic medals. In 2018, he set a new Canadian record in the indoor heptathlon with a score of 6,343 points. He also holds the Canadian record in the decathlon, another event that Coach Gramantik has coached athletes in.

- Michael Smith: Michael Smith is a former Canadian decathlete who was coached by Coach Gramantik in the 1990s. Smith set the world record in the decathlon in 1995 with a score of 9,015 points, a record that stood for almost a decade. Smith also won multiple world championships and Olympic medals in the decathlon and was considered one of the top decathletes in the world during his career.

Coach Gramantik’s philosophy has inspired generations of athletes and coaches alike by emphasizing the importance of hard work, consistency, and attention to detail. Despite his impressive “track record” (pun intended), Coach Gramantik remains humble and committed to helping his athletes achieve their full potential.

In this interview, I explored how Coach Gramantik’s upbringing shaped his love for sport, his university career path, and the start of his coaching journey. I found it especially eye opening to learn about the differences in the eastern European education systems and training philosophies from the Canadian systems and philosophies. This is just part 1 of our first interview out of an extensive series of interviews I plan on doing, but I hope this excerpt of the first interview gives readers some appreciation of his coaching philosophy.

One final item to note, Coach Gramantik has a thick Romanian accent that can be hard to understand at times. For this reason, instead of a video interview, a written interview is presented with adjustments to grammar, items cut out in certain segments, and responses shortened.

The Interview: Les’s upbringing

CR: I want to start by asking you – where were you born?

LG: I was born in a small town in Transylvania, which was part of Romania, at that time. It used to be an independent principality, to an independent country, so to speak. And then whoever won or lost the war changed that. It had a predominantly Hungarian population as it was almost 8 kilometres from what is the Hungarian border today and since the second world war. It has about 180,000 people now – but it used to be a lot less when I was born. It’s in a very insignificant location, nothing special. There’s a river that goes through the town and an even larger river and that’s about it. I grew up right on the highway that crosses Romania all the way from Budapest to Bucharest, all the way to Ivy. My father was a director of the theatre production in a very flamboyant production. Unfortunately, my father was all drinking and smoking. He smoked about 80 cigarettes a day – he chain smoked them – but he’s not alive anymore, but that’s a different story.

But so, what happened is the theater production went around the villages and they went to a village where my mother lived and was born. She was a 20 some year old woman and good looking so you know, he started to like her. Someone said to my mom – “You gotta be careful because that guy was on a 24 kilometre bus ride and the bus stopped seven times – and every time the bus stopped, he had a shot of hard liquor.”

Anyway, they got married. And I came along with a marriage that lasted four and a half years. And they divorced. I was four and a half. I hardly knew him. For years, I didn’t know much about him. And after he disappeared from my life, pretty much when I started to do well in sports in my mid teens, then he repeatedly appeared and started to hang around with us to come visit me.

My mom tolerated him messing around with the actresses he hired for a little, but not for long. And so the point that I always say about him is I inherited some of his attitude. He had such a light approach to life. Everything was “Oh fine! Whatever! Okay!” Everything had to be fun to the point that he ended up in Budapest with his sister, getting a surgery to cut half his lung off – and he climbed out the window of the hospital on the first level on the first floor because he wanted to have a beer. The doctors said he would live about six to eight months after the surgery. He lived 20 more years. Very bad shape, bronchitis, everything else, but he outlived everything they predicted okay?

Despite all these issues, he got up in the morning, dressed up nice, always a shirt and tie. Very pedantic and dressed up like he was going downtown. So I inherited some of it – some of his things inadvertently stayed with me right? I’m not him and I’m not, you know, I’m not good looking, I’m not musical, but that’s not the point, but his lightness is something I inherited and I used to be a lot more light in life than I am now. And so my mom basically took care of me alone. She worked in a factory, three shifts. Morning, afternoon, and night in a sewing factory. She was a seamstress. So every second week, I’d see her a lot but by the time I got up and went to school, you know, for kindergarten, it was often my auntie who looked after me. I spent tons of time alone as a kid of four or five years of age, I just stayed and played around the house with no babysitter.

CR: So how did you get food with no adults around?

LG: Well she always left some food. Like in the morning, she would leave a big cup of tea and then some bread or something. We were very poor. Very, very poor. She cooked a very steady menu, ha ha. Chicken soup on Monday. Meat left over from Sunday dinner for Tuesday. Invariably cabbage rolls on Wednesday, Thursday. Friday, sometimes pasta. But my grandfather didn’t like that we ate pasta, he said, “Poor people eat pasta.” It was an interesting time of my life. If I look back I have no real recollection of anything bad or good. Okay, it’s sort of just plain, okay. I keep telling people that I have never had a Christmas where I remember anything I got. We had no money. But Christmas day school was open. You had to go to school on Christmas Day. Oh, yeah. Socialism – so we had to, to do religious things.

CR: What are your memories of competing in sports in school?

LG: I had some friends and started to compete a little bit on school level formally at about 10 years of age. And I was pretty good early. So that’s how they discovered me so to speak, and I became part of a sports school system.

CR: What was the sports school like?

LG: Sport school was made up of the school and the track. You went to class for four hours, trained for two hours. That’s it, six hours a day. Then after that, home. Okay, so the first four hours of the day, eight to noon, was school, mathematics, language arts, everything that every kid should have. That was pretty much standard. And after that, depending on what your sport was, you started to kind of, you know, do more track or something else, you know, but track was a basic sport for everyone at that time, because that was the basis for everything right? Even for the volleyball players or basketball players, or soccer players – obviously. So when I say product or socialism, that’s how they envisioned their people growing up. Through sport, you get trained to be some form of disciplined person, right? Look at the army and those kinds of things. If you ever see a documentary called “Hitler youngend” – “youngend” meaning youth. And they show exactly what they did with us. They took kids, young men and boys, away in the summer, for a summer camp. We liked it. We loved it. We got to fight, wrestle, run, you know, it was all challenging physically. So that almost ended up being indoctrination, a little bit. “Brainwash.”

CR: Do you have a “favourite” or “fun” memory as a kid despite saying that you feel like your childhood was very plain?

LG: One memory is very interesting. It’s not a “favourite” and it’s not “fun”. But it is very eye opening. We had a teacher who taught like a shop class. He had a storage unit available outside and one day we peeked in there and saw that there was good wood in there. So one day, we broke into it, and took it. Man, we were punished! And he was fired. So it’s not a fun memory. So, I don’t really have that many fun memories but I had a favorite phys ed teacher, a young man. I just got an email two days ago from a former classmate who died just now. Istvan Kolumban was his name. He was very harsh and very hard and that’s what appealed to me… his sarcasm, his aggressiveness, his demands. He would put you in your place in no time, challenge you, hit you in the head. It was a different time.

CR: How did your mother influence how you are today?

LG: Oh, my mother taught me everything: discipline, punctuality, order, you know, respect, respect for women. Very important for her. If I was late coming home from somewhere, I got slapped. She was a hard woman and then she never got married until I got married.

She also was loving but not demonstratively loving. We never hugged each other. I never ever remember hugging her. And then it’s affected my life later because I’m not as open and I’m not blaming anything or anybody. Okay. For me to hug somebody now is easier now than then. But I think what she taught me as far as discipline, punctuality being on time, always finishing my work, to never quit.

CR: What was your favourite sport growing up?

LG: I loved sports. I loved soccer. I played all the time. It was my favourite by far… by far. I did track because I was pretty good at it. I was a pretty fast good sprinter. And I started hurdling early. At about age 15 or so, my old coach who was an amazing man left for vacation (for a month or month and a half) and a much older fellow that trained the hammer throw, called me up and told me, “Everyday we’re lifting”. And he meant lifting heavy. In about two months, I gained 25 pounds. So my coach came back, saw what happened, told me I couldn’t run, and made me do pole vault. So then I got the ball rolling and it progressed from there, and I lost some weight obviously. It is very much a social Russian system. We lifted a lot and heavy.

Click HERE for Part 2

Click HERE for Part 3