Starting from a Clean Slate with a Decentralized Team Sport Program

Scott Willgress, Canadian Sport Centre Atlantic

The Beginning

Rewind to the fall of 2016. I had been working in Halifax for 6 years with athletes and groups of varying levels. From private weekend warriors, to provincial level, next-generation, and a few Olympians in sports like sailing, sprint canoe/kayak, boxing, and artistic gymnastics. Don’t get me wrong, I loved working with these sports – I’m all about the challenge of working with a sport I have no history with and have never competed in myself. It’s easy to come into this situation with a beginner’s mindset when you truly are a beginner.

Hours spent watching video, reading peer-reviewed articles, and most importantly spending time in the coach boat/ringside/gym with athletes and coaches starts to give you a feeling of mutual understanding. Growing up in Calgary – where I earned my Master’s Degree in Exercise Physiology (2010) while learning from legends like Matt Jordan, Scott Maw, Dr. David Smith, Ryan Van Asten, and Matt Price– I barely knew the difference between the Olympic disciplines of kayaking, canoeing, and rowing, let alone what gybing downwind toward the leeward mark (google it) meant.

When I got a call from the CEO of the Canadian Sport Centre Atlantic asking, “Hey Scott, how would you like to work with Softball?” I was beyond stoked. Baseball was my sport growing up. I started at 6 years old, and only really stopped playing after we welcomed our second child in 2015 – at the age of 31. This was a chance to step right into a sport where I spoke the language. I could talk about turning two, hitting frozen ropes, and hopefully, help some of these athletes turn WTP (warning track power) into oppo bombs (google that too!).

Square One

As of 2016, softball (and the male Olympic equivalent, baseball) had been out of the Olympics for 2 full cycles (8 years). National team players continued to compete during the summers together with a World Championship being played every two years. Canada had managed to remain competitive internationally alongside powerhouses like Japan, USA and Australia, finishing with a bronze medal in 2 of the 4 worlds tournaments between 2008 and 2016. A big reason for this continued success, along with a steady group of players, was the leadership from Head Coach, Mark Smith.

Coach Smith is a legend in the Softball world, winning multiple world championships on the men’s side and is also a Nova Scotia native. Although we had never worked together directly, I came to find out Mark had watched me work with female Olympians like Ellie Black (Gymnastics), Jill Saulnier and Blayre Turnbull (Hockey), and Erin Rafuse and Dannie Boyd (Sailing). These examples of athlete support, plus my team sport background gave him confidence that I could be a great fit within his program.

Olympic Sport

In the fall of 2016, softball was officially reinstated as an Olympic sport for the 2020 Tokyo Summer Games. The athlete pool was spread out over the entire continent. Athletes were coaching at the NCAA level, playing NCAA ball, working full-time jobs, and players just training on their own. Although there was a strength program in place previously, the honour system was generally used, and testing was completed by the coaching staff.

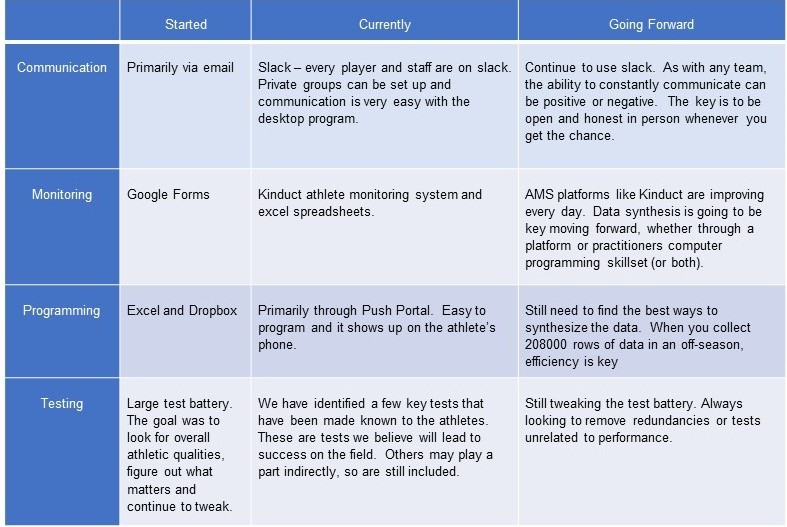

For the off-season of 2016-17, the main goal was to begin a culture of training in the off-season, with an increased focus on monitoring and physical testing. To begin, there was little to no budget for anything fancy on the S&C front. To achieve the monitoring goal, I went with a couple of no-cost options that I was comfortable with.

When it came to programming, I stuck with excel spreadsheets saved in individual Dropbox folders. The template was designed to allow players to enter weights lifted for each set and allowed me to complete individual check-ins to make sure athletes were completing programs and progressing well. For subjective monitoring, a google form downloaded and dropped into an excel spreadsheet was the logical choice. Each player got a Google form link and was instructed to save it the home screen of their phone along with a daily alarm. This was a good start for monitoring, but as with anything in the sport science world we were bound to evolve.

The summer of 2017 was my first opportunity to travel with the team. It was truly amazing for me to be part of the team for over 6 weeks of travel that included trips to Ontario, Chicago, Oklahoma City, and the Dominican Republic (see picture above). On top of my regular S&C duties, I took every chance I could to help on the field, from shagging pop flies during batting practice to catching throws during outfield drills. That summer was all about building relationships and gaining the trust of the athletes and coaches.

Through conversations, it became obvious that only a select few of the players completed all of the off-season workouts that had been sent out, and even less had been completed as intended. This is in no way a slight against the players. Even with the videos, emails, phone calls, and text messages that were exchanged all winter – nobody knew who I was, nor did they have any reason to trust me. It was clear a few things needed to change for the next off-season to be a success from a non-specific training perspective.

Making Moves

Starting in the fall of 2017, the testing, monitoring, and training process we now have in place started to take shape. As mentioned above, Softball has what is referred to as a “decentralized model” where the athletes compete together in the summer but disperse during the off-season for training. Some pockets of athletes exist in Canada (southern Ontario and the lower mainland of BC) and with the help of the Canadian Sport Institutes in those locations, we were able to set up training hubs with S&C and other support staff. That accounted for about 8 athletes, leaving 16+ on their own.

It was clear during the early off-season that buy-in was WAY up. I would attribute that in part to the relationships I was able to build that summer, but also to the emphasis put on off-season training by the coaching staff. Logging details were to be sent bi-weekly, check-ins were done regularly, and follow-ups were done when needed. Everyone was strongly encouraged to find a strength coach in their area and put me in contact with them.

How The Athletes Were Lifting

Another huge development in terms of our training effectiveness occurred in the fall of 2017. In conversations with the coaching staff, I stressed the importance of us knowing not only what the players were lifting, but how they lifted it.

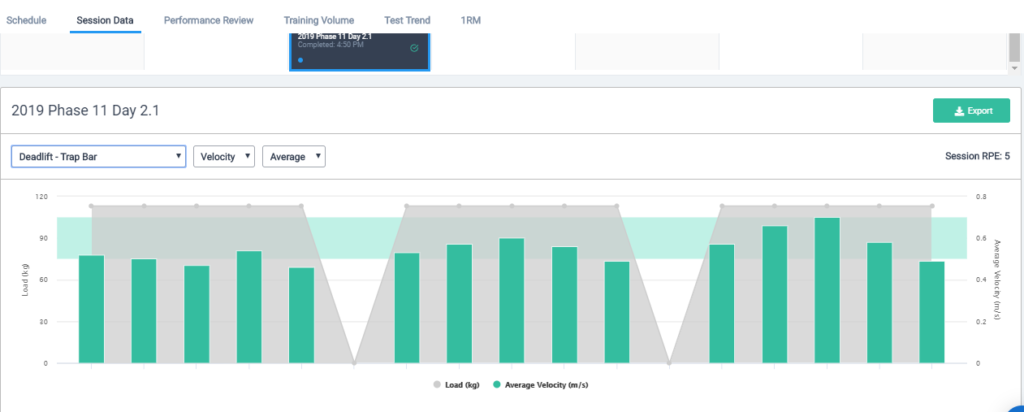

The local strength coaches could take care of technical proficiency, but monitoring intent, effort, and the resultant speed of movement was a tougher task. This was when we decided to invest in PUSH Strength – a Canadian company that makes wearable accelerometers to track velocity and power in strength training movements.

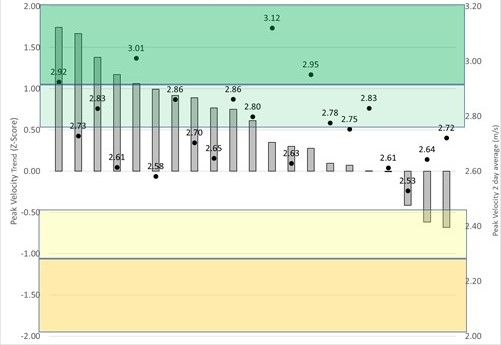

To start, I simply asked the athletes to complete 2 sets of 3 vertical countermovement jumps every Monday, as well as track the main lift of the day. By starting slowly, the players (and I) could get used to the technology together and eventually progress to more detailed use. By the end of the winter of 2018, I was using the Push Portal to program and monitor all aspects of the S&C program. Feedback about loading choices, the progression of programs, and information about adaptation to training could now be collected and used to inform decision making.

Picture above shows In-season lift load/velocity data from one athlete from Push Portal. The athlete was given a goal velocity range (green band) and used the feedback to help keep pushing the velocity from set to set. Green bars show velocity achieved.

Picture above is a snapshot of the whole team (each player is represented by one grey bar). Using a z-score to compare 2 days averages to 14-day average in vertical jump velocity allows us to see how each athlete is currently trending.

Gold Medal Profile

In the winter of 2017, we also began to collect bi-annual fitness testing data. The national team program had always done some form of fitness testing in the past, but it was usually run by coaches and in-depth records weren’t necessarily kept.

The fitness testing battery I came up with was partially based on the scarce literature available on softball, this primarily from Sophia Nimphius’ group in Australia, and partially based on my own philosophy on training. I firmly believe that for many athletes, maximal strength is the lowest hanging fruit. With proper time, effort, and consistency anyone can get stronger. This, in turn, should set them up for gains in speed and power.

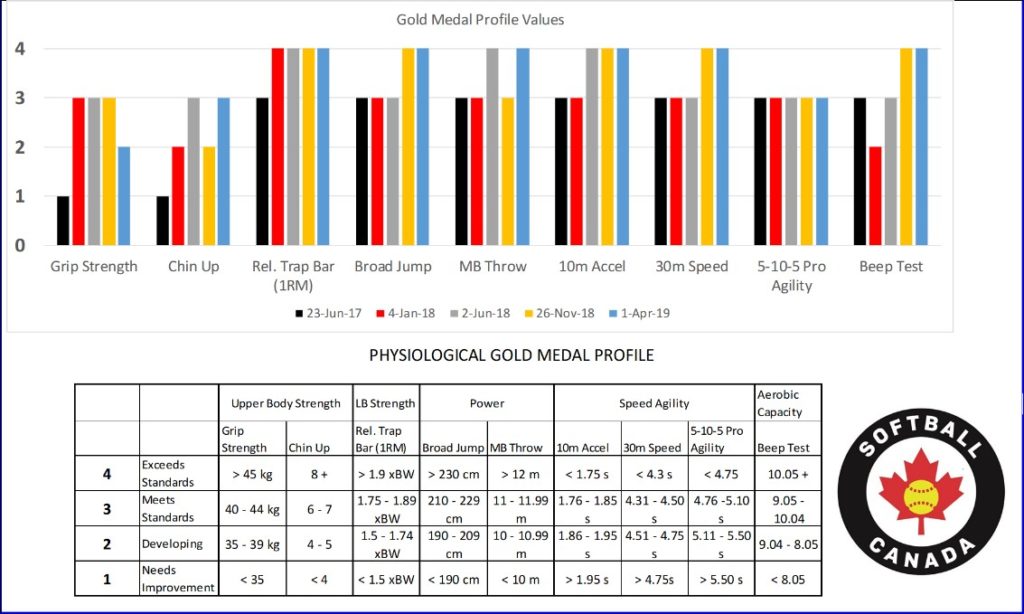

At this time Own the Podium (OTP, the Canadian Olympic system’s chief supporter and funding allocator) asked Softball to create a Gold Medal Profile (GMP). The purpose of the GMP was to set the program up for future success, by creating standards of excellence in areas of performance such as technical, tactical, physical and mental.

Using the GMP model, I was able to stratify the performance of players in each testing area. An average of each score could be used to calculate the player’s overall physical pillar score. After this round of testing it was suggested by a coach that each player should be at a 3 out of 4 as an average score. Knowing that this was unrealistic, a suggestion was made to set a goal to have a TEAM average of 3 out of 4 on the physical scale. This way players who were currently averaging in the 1.5 range, as well as players who already scored 3.5 on average both knew they could help their team by increasing their total score. On this team, this method was a huge success. Everyone was all-in for improving various physical markers to help the team raise the bar.

An example of using the GMP Values for player feedback over multiple testing periods. These scores can be averaged to represent a “Physical Pillar Score” for each player.

Monitoring

The final piece of the monitoring puzzle was put in place in the fall of 2017 as well. The google spreadsheet method of collecting had served us well, but it had limitations. After searching for a one-stop-shop athlete monitoring system, we decided on another Canadian company – Kinduct. With Kinduct we were able to import all our previous monitoring and testing data, as well as grant access to the full coaching and support staff. For monitoring, we used a modified Hooper-Mackinnon questionnaire as well as sleep and session RPE / training load information. From there, day by day trends can be seen, and with some excel trickery, the data can be visualized however you see fit.

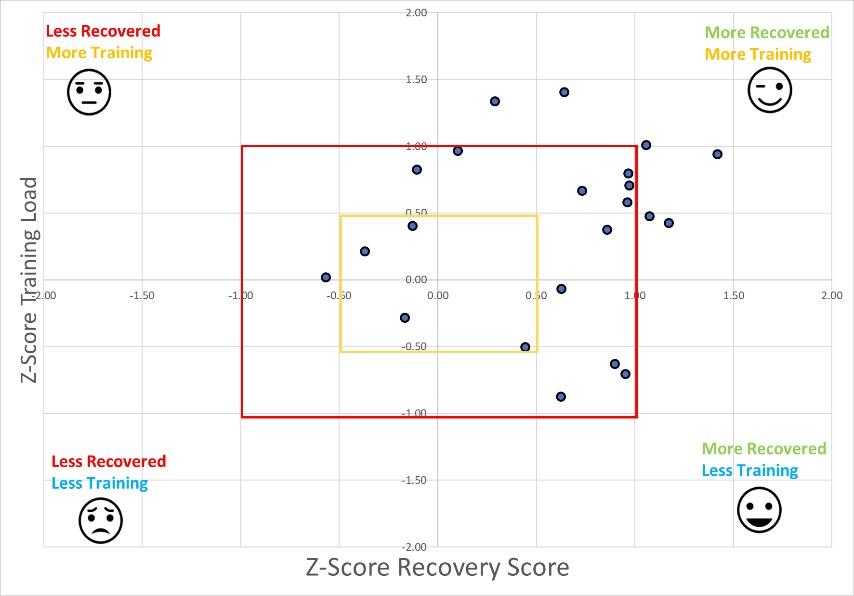

A quadrant style chart can be used, as above, to visualize how players (individually represented by a blue dot) are trending in terms of their total workload and subjective recovery.

By now you might be saying to yourself – “Wow, he collects a lot of data, but how does he use it, and does it mean anything?”. I firmly believe that if we don’t have a solid relationship with the athletes and coaches we work with, nothing can be accomplished. From a sport science and S&C standpoint, without a solid monitoring program in place, you are merely guessing. Especially if you are in a situation where you aren’t with the athletes regularly.

Having entry/exit physical test batteries is sometimes a necessity, however, a simple and consistent monitoring practice can answer a lot more questions and set you on a course for program individualization. My next entry will look at how collecting this data has influenced my thought process and programming over the last 2 years.

Special thank you to Darren Steeves and Cory Kennedy for their editing support and feedback.

Follow Scott here: twitter: SWIFTwillgress, instagram: sdubstrength