Facilitating Behaviour Change in an Athlete-Centered Coaching Environment

Since 2019, the Fitness and Performance (F&P) department at the University of Toronto (U of T) has been continuously improving how to measure student needs, and how to deliver programming that meets, and oftentimes exceeds, those needs. At the foundation of this shift are two concepts that are growing in popularity throughout the industry, (i) Athlete-centered coaching, and (ii) leveraging a behaviour change framework, like the COM-B model (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation factors of Behaviour change).

The University of Toronto recently conducted an extensive review of the Strength and Conditioning opportunities provided to students and student-athletes. An outcome of this review was to align with the University’s academic plan of treating every participant as a learner – whether in the classroom or within co-curricular activities. The mindset shifted from a focus on performance, to a focus on helping students learn to help themselves perform. This means creating a culture in which learning is the ultimate objective while facilitating confidence in translating that knowledge into action.

Providing an entirely athlete centered coaching environment is challenging to any coach, so our first initiative was implementing a structure that better enabled our programming and coaches to deliver on this objective. Secondly, we implemented the COM-B model to help all coaches better understand why some athletes were under-performing or unengaged during training – did athletes simply not understand the purpose behind what they were doing, or were factors such as motivation, opportunity, or individual capabilities holding them back?

In this article, we will take a brief look at the basics of Athlete-Centered Coaching and the COM-B model of behaviour separately. Examples will then be provided of specific strategies used at U of T to attempt to leverage these two concepts through various programming options, followed by some suggestions for implementation that any coach could use. The hope is that some examples provided can be an avenue of exploration that anyone working within the fitness industry can consider implementing.

Athlete-Centred Coaching

An Athlete-centered coaching model puts the athlete in the driver seat of their learning and promotes the development of the athlete from a holistic perspective (Milbrath, 2017), instead of exclusively measuring physical traits and performance. Athlete-centred coaching can be defined by “a style of coaching that promotes athlete learning through athlete ownership, responsibility, initiative and awareness” (Pill, 2018). Some of the benefits of adopting an athlete-centered approach include promoting athlete autonomy, accountability, empowerment, and providing an environment that promotes informed participation (Milbrath, 2017). While much research and terminology focuses on ‘athlete’ centered, this style of coaching can be applied to anyone that is engaging in a coaching environment, not solely focused on athletes.

Providing athletes with an active role in the decision-making process can result in them taking greater responsibility and ownership of their performance, which is believed to assist in the learning and retention of technical aspects (Nelson et al, 2014). This concept is not a new one, and certainly not exclusive, to the coaching profession – research exists that highlights the benefits of involving employees in decision-making processes to improve engagement, morale, and job satisfaction in various corporate settings (Markos, 2010, Konrad, 2006).

The U of T F&P department has made it a priority to leverage these athlete-centered concepts in order to provide a learning environment that encourages athletes to feel ownership over their activity and thus be confident in playing a leading role in their physical development. An athlete-centered style of coaching can provide an environment in which a behaviour change model, such as the COM-B model , can be successful through both understanding and involving your athletes.

The COM-B Model

Behaviour change is challenging, and is something coaches strive to have an impact upon. There are many theories of behaviour change, however, the COM-B model of behaviour is a simple way to view behaviour change and can provide a checklist to assist with a participant’s behaviour change over the long term.

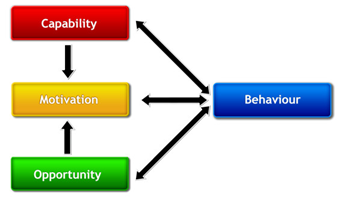

Mitche et al (2011) evaluated many different frameworks of behaviour change for their comprehensiveness at classifying behaviour change interventions. Through the analysis of these frameworks and identifying the limitations, a new behaviour change framework was developed. This new framework is the behaviour change wheel and is a 3-tier system to identify behaviour change interventions. At the heart of the wheel, and the focus of this article, is the 3 components that make up the COM-B system. These components are Capabilities (C), Opportunity (O), and Motivation (M). Capability is the individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in an activity; opportunity is the factors external to the individual that make the behaviour possible; motivation explains the brain processes that direct behaviour (Mitche et al, 2011). These components can interact in many ways to affect the behaviour of an individual as noted in the diagram below (Mitche et al, 2011).

by S. Michie etc al, 2011, Implement Sci, 6(42), https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3096582/.

Copyright 2011 by Michie et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

The second tier of the behaviour change wheel describes 9 intervention functions that can be used depending on the specific COM-B component identified as lacking. Finally, the third tier, or outer layer of the wheel identifies the policy categories that can support the delivery of the intervention. This article will only focus on the first tier of the wheel – the COM-B system. More information about the entire wheel can be found in the book “The Behaviour Change Wheel, A guide to designing interventions.” by Susan Michie, Lou Atkins and Robert West.

Let’s take a look at the model with respect to an individual wanting to engage in physical activity. An individual may feel limited by their abilities in a weight room setting by not knowing how to use specific equipment. This can impact their motivation to go to the gym. However, if provided with the opportunity to learn about the equipment, say through a personal trainer or gym orientations, their confidence and motivation may increase, leading to an increased likelihood of visiting the gym.

Examples of Athlete-Centred Coaching and COM-B Working Together

It is the belief of the U of T F&P team that engaging in an athlete-centered style of coaching can lend itself well to facilitating behaviour change within the framework of the COM-B model. The following are a few examples of how we are attempting to put these two concepts into practice.

One of the objectives of our recent revamp of programming on our recreational side is to address a series of common capability barriers. To start, let’s cover (i) a lack of awareness around programming and (ii) a participant being unsure of how to exercise ‘properly’. Personal training would address these barriers, however the costs associated with personal training also represent a common barrier for a lot of students. Therefore, we introduced two low cost alternatives with Big Hiit sessions and Squad training sessions. Each of these sessions provides high quality coaching and educational content, yet each has a slightly different focus – Big Hiit providing the high intensity, conditioning focused workout, while Squad training provides the more traditional weight training workout. In both sessions, participants can choose from a range of progressions and regressions that suit their current needs while being coached up on how these movements are relevant to their life. This example looks to address the capability barriers of cost and lack of knowledge and awareness in the gym environment by using the opportunity to provide low cost, group training sessions, programmed to be participant centered.

A third common barrier observed among individuals is the lack of motivation to use a weight room facility due to intimidation and lack of understanding around equipment usage. Over the past 18 months, the fortunate opportunity to completely redesign one of the weight rooms and field house facilities on campus presented itself. A focus during the redesign was an attempt to tackle the intimidation barrier by making the space inviting and accessible to any student on campus. One strategy was setting up cardio equipment around the perimeter of the weight room, positioned to look in towards the weight equipment. The purpose behind this was to provide a participant with the opportunity to ‘learn through observation’ by viewing others using different equipment and performing various exercises. As one consistently observes the different equipment in use and participants performing various exercises, they may gain the confidence to try things out for themselves.

Looking now to our work with the varsity student-athletes, a focus of ours has been to address perceived lack of mobility (Capability) through the use of a mobility screen and subsequent education and intervention (opportunity). A common discussion topic we’ve heard over the years is that a perceived lack of mobility is affecting certain movements – read: ‘I am unable to squat because I do not have hip mobility’. Over the past 3-4 years, the department has been putting every student-athlete through a mobility assessment to truly identify if there are mobility restrictions and the subsequent implications for activity. The mobility assessment looks solely at mobility around shoulders, hips, and ankles, and student-athletes are provided a letter ranking – A, B or C – for each joint. What we have come to find over the 500+ student-athletes who have completed the mobility assessment is that rarely is ‘lack of mobility’ the actual issue. The more likely issue facing the student-athletes is the strength to control the areas around the joint and the individual awareness of how they are moving. Students are then provided with specific exercises to help address the mobility, strength and control at each joint, based on their specific letters. Time is spent educating the student-athletes about the impact of their score in relation to sport performance and also everyday movement. We are looking to impact the student-athlete’s motivation to work through movement patterns and ranges of motions that were previously thought unattainable.

The final example draws upon the general concept of student athlete buy-in to strength and conditioning programming. When we think about the concept of buy-in, we are looking at an athlete’s willingness or motivation to participate in a specific activity. As seen in our model, motivation has a direct relationship on behaviour change – greater buy-in means a greater likelihood of changing long-term behaviour. This past year has afforded us time to develop and implement speed programming that is almost completely student-athlete driven. A couple of the barriers we’ve experienced in the past are student athletes not understanding applicability to their sport performance and mimicking their teammates without thinking about their own capabilities. This year, the programming was structured in a way that let the student-athletes define their own path. They were provided with the opportunity to choose movements related to their specific sport as well as areas they identified as wanting to improve upon based on their perceived capabilities. The session was divided into sections with a specific focus in each section (such as plyometrics, medball power work, sprints, and agility), but the student-athletes were given choices within those sections. As an example, a basketball player may choose vertical based plyometrics with short ground contact time, while a hockey player may opt for horizontal and lateral based plyometrics with long ground contact time. Similarly, a rugby player may choose a cutting drill that spans 20-30 yards, while a volleyball player may choose a cutting drill that spans 5-10 yards. After taking time to adjust to taking control of their workouts and making decisions, we observed the athletes putting more effort into these sessions, asking insightful questions about the relationship to sporting performance, and taking more ownership of their training.

The above examples have all been specific to the environment at the University of Toronto, however the overarching concepts can be adjusted to suit any coaching environment.

Integrating Participant-Centred Coaching Principles with the COM-B Model

Coaches and trainers want to see their athletes improve and want to play a part in driving a long-term change of behaviour. Feel free to use the below suggestions to introduce these concepts into your coaching routines:

- Identify the capabilities of your athletes/team: work with your group to identify if they have the knowledge, skills and abilities that are needed to engage in a specific behaviour?

- Within your specific environment and scope, identify some opportunities you can provide that may speak to the specific capabilities that were recognized above.

- Engage – put your athletes at the forefront of development. Question their desires and motivation, try to have them identify their barriers to improvement and change. Athlete involvement, as mentioned earlier, can lead to more ownership over activities and thus drive motivation and behaviour change.

- Evaluate – Once strategies are put in place, evaluate if it is achieving the results in which you were aiming. Are athlete’s attitudes towards the specific activity changing? Are there changes in a specific behaviour? It’s important to keep in mind this is a long process that may take time to evolve.

- Finally, involving athletes in the decision-making process, and following an athlete-centred style of coaching is messy and chaotic. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Start small and adjust as you go. It may take more energy and time, but the rewards to be gained are worth it.

The COM-B model represents only one of several frameworks that can be leveraged to encourage behaviour change. We chose COM-B at U of T because of its simplicity and how easily we could integrate it into our athlete-centred coaching strategies, but that does not mean other frameworks are inferior. We are constantly iterating on our programming and delivery in an effort to offer the best possible experience for student athletes at all levels, and I hope the examples provided in this article have demonstrated how simple changes can sometimes yield valuable results. I also hope you are encouraged to do your own independent research on the various behaviour change models and find simple and creative ways to introduce their benefits into your own coaching.

Alanna Coulson is the Lead Coach of Fitness and Performance at the University of Toronto and oversees the implementation of Strength and Conditioning for the Varsity Blues program that encompasses 22 teams. This role also entails the development and implementation of fitness programs focusing on physical literacy and everyday health that is accessible to the entire student, staff, faculty and community population of the University of Toronto. Alanna completed her Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology at McMaster University and her Masters in Human Kinetics with specialization in Intervention and Consultation at the University of Ottawa.

References

Konrad, A. M. Engaging employees through high involvement work practices. Ivey Business Journal, 2006;March/April.

Markos, S. Sridevi, M.S. Employee Engagement: The key to improving performance. International Journal of Business Management. 2010 Dec;5(12):89-96.

Michie, S. Atkins, L. West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel, A guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback Publishing; 2014.

Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M. & West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Sci. 2011 Apr;6(42).

Milbrath, M. Athlete-Centered Coaching: What, why, and how. Track Coach, 2017 Jan;218:6939-44.

Nelson, L., Cushion, C.J., Potrac, P., & Groom, Ryan. Carl Rogers, learning and educational practice: critical considerations and applications in sports coaching. Sport, Education and Society. 2014 Jul;5(19):513-31.

Pill, S. Introduction. In: Pill, S. Perspectives on Athlete-Centered Coaching. New York: Routledge; 2018. P 1-5.